Executive Summary

Both union and non-union employees have the right under federal law to engage in discussions with their colleagues about their terms and conditions of employment, including wages, hours, and working conditions; and to join together to improve these conditions. Low-income, low-educational-attainment, and non-white workers are least likely to feel comfortable discussing workplace conditions with their colleagues.

These rights are often violated. Research suggests that as much as half of the US workforce have been “discouraged or prohibited” from discussing pay.

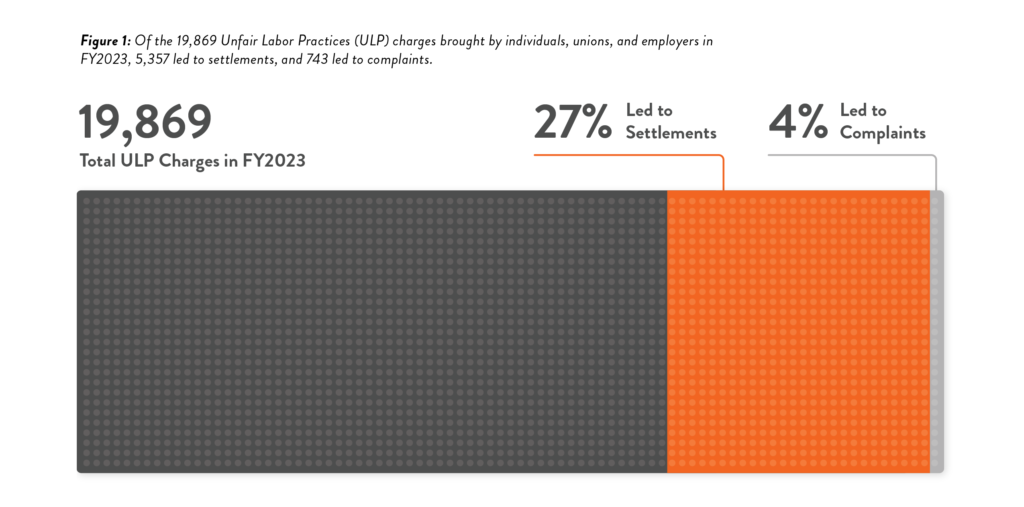

Meanwhile, neither workers nor unions can enforce these rights by suing the employer. Rather, it’s up to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”) to bring a complaint against the employer, and most claims that workers bring to the NLRB do not result in such a complaint or a hearing in front of an administrative law judge.

This report analyzed all decisions issued by administrative law judges between 2015 and 2020 on “concerted-activity” retaliation complaints brought by individual workers to the NLRB. These were complaints brought by workers who lacked union representation, where the worker says that they tried to band together to improve working conditions but faced retaliation by their employer.

Findings

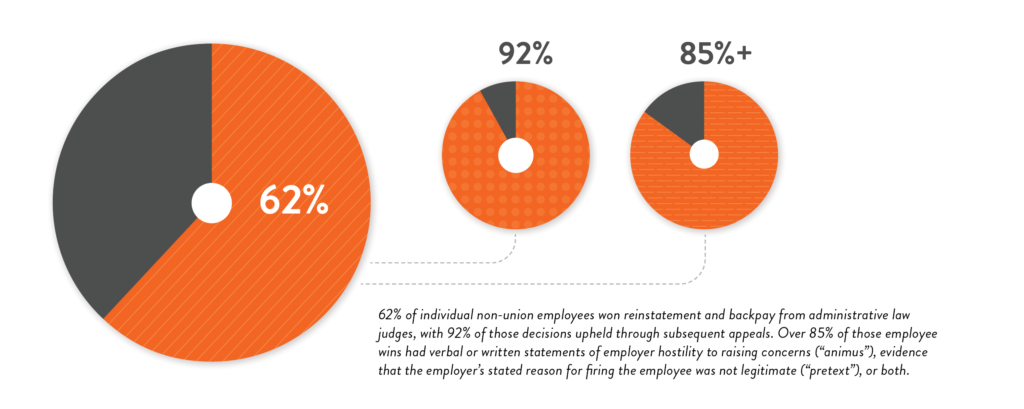

- 62% of individual non-union employees won reinstatement and backpay from administrative law judges, with 92% of those decisions upheld through subsequent appeals.

- Over 85% of those employee wins had either verbal or written statements of employer hostility to raising concerns (“animus”), evidence that the employer’s stated reason for firing the employee was not legitimate (“pretext”), or both.

- Circumstantial evidence that the employee was treated unfairly was rarely sufficient without additional evidence of pretext or animus.

- Although most credibility determinations in our sample were assessed against the employer, in 61% of employee losses in our sample, the judge expressly identified the charging-party employee as less credible than the employer or employer’s witnesses.

- When employees lost, the most common reason was that their actions were not sufficiently “concerted” or directed at mutual aid. In other words, the employee’s actions were done on their own, and not with and on behalf of co-workers.

Implications for Workers

- Overall, our analysis suggests that the NLRB does vindicate strong claims of retaliatory discharge for efforts to improve working conditions if the complainants can get to an administrative law judge hearing. Although Board-level policy decisions may vary dramatically across Administrations, the average employee win rate before an NLRB judge is more consistent.

- Our data indicates that on these claims, neither the administrative law judges nor the Board are rubber stamps for the NLRB General Counsel who prosecutes these claims.The General Counsel brings only the strongest complaints, and yet administrative law judges still reject nearly four out of ten such claims. The Board overwhelmingly affirms decisions when presented with appeals from both sides.

- Workers need to make sure to raise any concerns both with co-workers and about things that affect co-workers. That is, it can’t be just one worker complaining about her own situation. And documentation of these conversations will help if retaliation follows. Though employees must walk a fine line to frame complaints in a manner that demonstrates collective concern without risking retaliation, the issue should be framed as a complaint, not merely a suggestion, in order to be legally protected.

Legal and Policy Considerations

- While overall win rates before judges are encouraging, workers are entirely dependent on the NLRB to even bring a complaint to a judge at all. Even successful claims take months if not years to get limited relief, in part because of the agency’s chronic underfunding. Congress should increase enforcement of this right by fully funding the NLRB and passing the Protecting the Right to Organize (“PRO”) Act, which would give workers the ability to file a suit against their employer and increase penalties for employers.

- In the meantime, worker advocates can focus on expanding access to these rights by continuing to push the NLRB to recognize the full scope of the rights implied in the Act. Expanding the “inherently concerted” doctrine to include discrimination and health and safety complaints is both consistent with the law and would increase the accuracy of outcomes on such concerted-activity claims.

- Additionally, holding employers accountable for lack of process or consistency is crucial, challenging the common “equal-opportunity jerk” defense and ensuring fair treatment irrespective of an employer’s management practices.

- Finally, the NLRB should make sure that administrative law judges recognize the power imbalances that make raising concerns in an “at will” workplace difficult and not hold employees to an unrealistically high standard of proof in showing concerted activity.

Full Report

Fact Sheet: The Importance of Protecting Worker Voice and Concerted Action

Introduction & Overview

Most Americans have the right to talk to their co-workers about their wages and working conditions. But many Americans just don’t know enough about their rights to feel confident having those conversations. Recent surveys suggest that most workers are uninformed or misinformed about their legal rights at work, and employers often exploit that lack of information to discourage workers from raising concerns.[1] Low-income, non-white, and less-educated workers are least likely to feel comfortable discussing workplace problems with their co-workers.[2] Fear of employer retaliation for raising common concerns about working conditions is a major factor that prevents workers from coming forward. A study of California workers revealed that nearly half of those who experienced workplace violations never reported them to anyone, internally or externally – and among those who did not report, a majority indicated that fear of retaliation factored into their decision.[3]

The fear of retaliation is often justified. In American work culture, a squeaky wheel is as likely to be met with the boot as with grease. Depending on the underlying complaint and the worker’s socioeconomic status, they may qualify for free legal aid to challenge their termination, or they may be able to hire an attorney through a contingency fee arrangement. But most people in the United States are subject to at-will employment, meaning they can be fired for any reason without warning or explanation.[4] And while getting fired for blowing the whistle on illegal activities may be prohibited, complaining about important issues like low pay or insufficient staffing doesn’t necessarily confer those same rights.

Unless, that is, you’re talking about it with and on behalf of your co-workers. Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) provides that “employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.”

This means that even employees without a union have the right to engage in discussions with their colleagues about their terms and conditions of employment, including wages, hours, and working conditions. They also have the right to join together to improve these conditions through actions such as a protected strike or picketing, as long as these actions are conducted in a peaceful and lawful manner – regardless of whether they have a union.

Most private employees in the United States have the right to talk to their co-workers about working conditions under the NLRA, and to raise those concerns on behalf of their co-workers to management, without retaliation from their employers.[5] The rights are exclusively enforced through the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”), and the remedies are limited to actual damages. Still, the NLRB can demand reinstatement and backpay for a wrongly terminated employee, and an employee can pursue an NLRB charge regardless of whether they signed an arbitration agreement.

But it is unlikely that many employees even know that they have these rights, let alone where to go to seek redress when they are wronged. This is unfortunate, because, in the words of the NLRB’s current General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo, “[the NLRB is] not pro-union. We’re not pro-employer. We’re pro-worker.”[6] Truth be told, we were skeptical when we started this project. The NLRB is famously underfunded and subject to political winds. But we set out to assess the viability of pursuing an individual charge against a non-union employer at the NLRB.

To do so, we reviewed every concerted-activities claim, brought by an individual in a non-union workplace, addressed by Administrative Law Judges (ALJs) from June 2015 to August 2020. The numbers we found support Abruzzo’s claim: employees challenging unfair termination in NLRB proceedings won 62% of the time before ALJs, with almost all wins meaningfully sustained through subsequent Board decisions and processes.[7] We also tracked which factors the judges paid most attention to making their decisions, and where the cases failed, to try to understand what makes a difference in outcomes.

Our underlying goal – increasing awareness of this right and the NLRB’s role in protecting all workers – is about more than resolving individual retaliation claims, as important as those are. Encouraging co-workers to talk to one another about their working conditions has greater potential to correct the imbalance of power between employers and employees than any individual case, and the breadth of Section 7 protects much more than conversations about wages and hours. Conversations with co-workers are also essential for identifying patterns of systemic discrimination, harassment, and health and safety violations. They offer crucial associational benefits at a moment of increased polarization in our society.[8] They contain the seeds of future labor campaigns and offer benefits to employees themselves. A sense of power at work is strongly correlated not only to job satisfaction but with overall happiness, and free information-sharing among employees can also create a more productive workplace.[9] After pay satisfaction, workers’ assessment of the power they had to change working conditions was the strongest job-related predictor of overall job satisfaction.[10]

But before encouraging workers to talk more about working conditions, we must ensure that they have a meaningful path to enforce their rights and challenge employer retaliation. The data ultimately supports cautious optimism for how such claims fare at the NLRB. Although relatively few of these cases are adjudicated by the NLRB each year, our analysis of these claims suggest that the NLRB can be a promising avenue for employees to successfully challenge retaliatory discharge after complaining about their working conditions.

Background

I. How Federal Law Protects Workers Trying to Improve Working Conditions

The National Labor Relations Act (“the Act”), also known as the Wagner Act, was enacted in 1935 to protect workers’ rights to form and join unions, engage in collective bargaining, and take part in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or mutual aid and protection. The law was created in response to decades of worker unrest, strikes, and violence, and it aims to promote industrial peace and stability by balancing the rights of workers and employers. At its core, the Act reflected the understanding that empowering workers to discuss their working conditions with one another is a public good, something that yields benefits not only for workers themselves but also for the economy and country as a whole.

The Act set out to bolster worker power and facilitate peaceful employee-employer relationships by “protecting the exercise by workers of full freedom of association, self- organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of their employment or other mutual aid or protection.”[11] The Act expands on the specific rights that follow from this goal in its preceding sections, which articulate the rights and limitations on employers, unions, and non-unionized workers. The relevant section for our purposes is Section 7, which articulates the protected rights of non-unionized workers:

“Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection, and shall also have the right to refrain from any or all of such activities except to the extent that such right may be affected by an agreement requiring membership in a labor organization as a condition of employment as authorized in section 8(a)(3) [section 158(a)(3) of this title].”[12]

The right most relevant for non-union employees tends to be the right to “engage in other concerted activities” for “mutual aid or protection.”[13] This may take many forms, including discussing wages with colleagues, collecting petition signatures to raise awareness over safety issues, and emailing coworkers with concerns about company policy. As is clear from the statute, this right is distinct from and broader than anything directly related to union organizing, and applies to all private-sector employees with a few limited exceptions.[14]

Violations Under the Act

When an employer infringes on this right or other rights articulated in the Act, they have committed an unfair labor practice. All unfair labor practices are described in more detail in Section 8 of the Act. Those most relevant to non-unionized workers are:

8(a)(1): “It shall be an unfair labor practice for an employer– to interfere with, restrain, or coerce employees in the exercise of the rights guaranteed in section 7”

and

8(a)(4): “It shall be an unfair labor practice for an employer– to discharge or otherwise discriminate against an employee because he has filed charges or given testimony under this Act”

Enforcement of these rights is solely entrusted to the National Labor Relations Board, an independent government agency that processes NLRA-based claims. There is no private right of action under the Act. The Board has five Members appointed by the President, with Senate advice and consent, to five-year terms, with the term of one Member expiring each year. The agency is also overseen by a General Counsel, independent from the Board but also appointed by the President to a four-year term. The General Counsel is responsible for investigating and prosecuting unfair labor practices before the agency’s Administrative Law Judges (“ALJs”). The decisions of the ALJs are subject to review by the Board, which acts as a quasi-judicial body deciding cases based on the review of the ALJ’s determination and records.

Essentially, the NLRB is divided into several different bodies, which collectively act as investigators, prosecutors, and judges. The structure and role of the NLRB becomes clearer through examination of the process of how an individual brings a charge against an employer under the Act.

II. The NLRB Process

Charge Filing Process

An individual looking to bring a claim against their employer must first file a claim within 6 months of the offense with a NLRB Regional Director. The Board itself is headquartered in D.C., but has regional offices tasked with investigating charges that come in from their region. The Regional Director investigates the employee’s claim to determine whether existing evidence substantiates the charge. Most charges are settled, withdrawn, or dismissed by the Regional Director at the investigation stage. If the evidence is sufficient, the agency attempts to facilitate a settlement between the parties. If settlement efforts fail, the charge becomes a complaint and moves forward.

Complaint and Hearing Process

If the Regional Director finds that the evidence is sufficient, they will file a complaint on behalf of the employee in the name of the Board. The NLRB General Counsel then acts as a prosecutor of the case in a hearing before an NLRB Administrative Law Judge, where both sides can present witnesses and other evidence to support their claims. The Administrative Law Judge will then issue a decision, in which they may either find that the employer violated the act and impose a remedy, or, if they find that the employer did not violate the act, dismiss the charge.

After the ALJ

All Administrative Law Judge decisions are subject to review and revision by the Board. The Board may affirm, dismiss, remand, or modify the ALJ decision. Once the Board renders a final decision, a charging party or respondent may seek further remedy by petitioning appellate courts for review. The parties can of course settle at any point in the process and seek dismissal of the claims.

Board Review and Appeals

A charging party who is successful at the hearing will almost certainly see the ruling substantively upheld by the Board and in any subsequent appeals in federal court. In practice, the Board rarely changes the substantive effect of an ALJ opinion on retaliatory discharge even when they disagree with the ALJ’s reasoning. Some of this may be due to the weight afforded to credibility determinations throughout the proceedings; the Board’s policy is not to overrule ALJ credibility determinations unless the “clear preponderance” of “all the relevant evidence” convinces the Board that they were incorrect.[15] When the Board adopts a ruling, the appeals court applies a substantial evidence standard to overturning Board decisions. Factual conclusions drawn by the Board will be affirmed if supported by substantial evidence, and the Board’s application of law to facts will be affirmed unless arbitrary or otherwise erroneous.[16]

Overall Data on NLRB Charges and Representation

The NLRB receives between fifteen and twenty thousand unfair labor practice charges each year, including those filed by unions and employers. On average, only about a third of those charges lead to settlements, and under 1500 of the charges lead to complaints.[17] Over half of the charges are withdrawn or dismissed. The NLRB does not break this down by the type of charging party—individuals, unions, or employers—so it is difficult to say whether individuals are more or less successful than this overall picture. Regional NLRB staff conduct investigations into charges to determine probable merit; most cases where probable merit is found will go on to settle by agreement of the parties. If settlement fails, the Regional Director will issue a complaint. NLRB attorneys do not officially represent the employee until a complaint is issued; until then, a non-union worker has no specific representative to protect their interests in the process unless they have separately retained counsel.

Notably, separately retained counsel appears to be an outlier in cases brought by individuals in a non-union workplace. In the successful cases we identified, over half of the complainants did not have separate counsel representing them at the ALJ hearing.[18] Still, the rate of representation at ALJ hearings was higher (39%) in successful cases than in unsuccessful cases (18%). Of course, it may be that successful cases had stronger evidence, even without counsel, so we cannot say definitively whether retaining counsel increases the likelihood of success.

It is not surprising that many charging parties do not have counsel to represent them in these matters. Without a private right of action that provides for attorney’s fees, workers have to rely exclusively on contingency fee arrangements. And as noted previously, remedies under the Act are limited to make-whole remedies like reinstatement, back-pay, and possibly consequential damages—making these cases not particularly attractive for many lawyers.[19] The process itself can be more uncertain than claims that can be brought in court, as it is up to the agency whether to bring a claim. There are attorneys who take these cases and help their clients succeed, as evidenced in the sample we reviewed. But the relatively low rates of representation at these hearings merit closer attention to the effect this institutional incentive structure has on vindication of workers’ rights. In this paper, though, we focus on how doctrine that developed in the context of union organizing protects employees who frequently lack either union support or legal representation.

Methodology & Legal Framework

We determined that the best access point for gaining such understanding would be through an analysis of ALJ decisions. We chose ALJ decisions for a number of reasons: first and foremost because the ALJ decision is typically the first (and often only) substantive merits determination on most cases. Charge documents, investigation materials, settlement proposals, and generally all documents prior to the hearing are typically not readily available to the public, but ALJ decisions are separately searchable via the NLRB’s website. Second, because ALJ appointments and removals are insulated from political decisionmakers (unlike Board members),[20] we hypothesized that their application of the law would be less likely to vary with the political winds. Third, ALJ decisions tend to go through the entirety of the relevant legal analysis, instead of focusing on the points of contention, as Board decisions (which resemble appellate decisions) often do.[21] Finally and critically, most ALJ decisions are adopted or ultimately affirmed by the Board, meaning these opinions are typically also the final word as to the merits of the claim. Of the sixty-three employee wins we catalogued, only five were subsequently overturned—and those five include two cases that were ultimately dismissed on jurisdictional grounds.

Identifying a recent and representative period of time in which to evaluate these decisions presented another challenge. The extraordinary political polarization of the Trump election and administration, combined with the unprecedented challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, the unpredictable nature of the timing for case resolutions, and small overall numbers of cases made it difficult to find a representative time period from which to pull a generalizable sample. Ultimately, we reviewed 101 individual claims decided by ALJs over the course of five fiscal years, from June 2015 to August 2020, spanning the end of the Obama administration, transition to, and most of the Trump administration. Ending in mid-2020 kept claims related to the pandemic out of the sample, and starting in mid-2015 meant that most of the ALJ decisions would be reviewed by a more conservative Trump-era Board. To the extent this sample is biased, we would expect the bias to slightly favor employers. Nonetheless, as discussed infra, we found that charging parties were mostly successful, and that very few ALJ decisions were substantively overturned on review. The percentages of wins versus losses for employees were also similar across all five years.

Finally, we zeroed in on retaliatory termination as the key action for understanding how these claims play out. Determining whether terminations are indeed unlawful is, of course, central to employment law. Although the specifics of each claim vary by statutory framework, most employment law claims come down to a consistent pattern: a worker is fired and says the firing is illegally motivated, the employer claims the firing is legitimate, and the adjudicator decides who to believe. We coded for the presence or absence of different factors (in these cases) to gather insight into how they impact ALJs’ analyses. Our intention was to better understand what makes an employee claim successful and which arguments are most persuasive.

Looking at these claims should give us a toehold for comparison to the success rates in analogous actions in discrimination and whistleblower retaliation cases, even as those cases are prosecuted in different forums and under different standards. And unlike other areas of NLRB doctrine, the legal framework NLRB ALJs use to evaluate these types of claims has relied on a set of core principles that have remained largely unchanged for over 40 years.

III. Prima Facie Case

For nearly a half-century after the NLRA’s enactment the Board did not apply any consistent causation test for discriminatory discharge claims.[22] In 1980, the Board adopted a burden-shifting regime borrowed from Mount Healthy School District v. Doyle – a Supreme Court case involving constitutional rights violations by public sector employers.[23] The repurposed test described in Wright Line has largely controlled analysis of these claims ever since.[24]

Threshold Question – Adverse Action

As a threshold question, the employee must prove that they have in fact suffered some adverse action. In the majority of cases, this is undisputed. In discharge cases, for example, it is often obvious that there has been an adverse action. In other cases, the employer may challenge the characterization of the adverse action as a termination, arguing that the employee instead quit, or the employee may seek a claim of constructive discharge alleging that they were forced to quit. In still other cases, employees may challenge the failure to renew a regular contract as an effective form of termination, or otherwise seek to show that a non-termination action like a transfer, reduction in work hours, or change in job responsibilities constituted an adverse action.[25]

Wright Line Framework

Once an adverse action is established, attention turns to whether the employer took that action for a lawful or unlawful reason. At this point, ALJs apply the NLRB’s Wright Line framework to evaluate the causal connection between the adverse action and unlawful reasons—here, because the worker engaged in “concerted activity.”

The doctrine from Wright Line consists of two main steps. First, the General Counsel, who represents the employee, must establish a prima facie case that the employer’s decision to take the adverse action was motivated, at least in part, by activities protected by the NLRA. In order to meet this initial burden, the General Counsel must show that:

(1) the employee was engaged in “concerted activity for the purpose of mutual aid or protection” (otherwise known as “protected activities”),

(2) the employer knew of such activities, and

(3) the employer harbored animus towards such activity.

If the General Counsel is able to accomplish this, the burden then shifts to the employer for the second step. The employer is given the opportunity to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that it would have taken the same action absent the protected activity.[26] Therefore, the protected activity did not “cause” the adverse action.

IV. Employers’ Motivation: Animus & Affirmative Defenses

Employers can defend themselves by showing that they made the decision for legal reasons or, if the action was illegally motivated, that the employee’s actions were nonetheless so inappropriate as to lose the protections of the Act. If, for example, the employee used discriminatory slurs, or threatened violence while engaging in concerted activity, their activity will lose the protections of the Act.[27] If the employer is able to successfully mount an affirmative defense, they will not be found to have violated the Act, and the employee will lose their case. If the employer is not successful in demonstrating they would have taken the same action absent the protected activity, or in showing that the employee’s actions were so egregious as to lose protections under the Act, they will be found to have violated the Act, and the employee will prevail.[28]

Animus and the Tschiggfrie Factors

In most cases, ALJs considered the same or similar factors when determining both the presence/absence of animus and whether the employer would have taken the same action absent the protected activity. We tracked analysis on the eight factors are most frequently considered:

(1) verbal or written indications of animus

(2) suspicious timing

(3) false, shifting, or pretextual reasons

(4) failure to investigate

(5) practice departures

(6) past tolerance

(7) disparate treatment

(8) credibility.

Most of these factors are drawn from Tschiggfrie Properties, Ltd., 368 NLRB No. 120 (2019), which was often cited by ALJs as guiding their analysis in the latter cases in our sample.[29] We also added factor 1, verbal or written indications of animus, as this factor accounts for the consideration of direct evidence presented at the hearing, while the rest of the factors mostly account for circumstantial evidence.

Analysis

In the analysis that follows, we identify patterns based on the data we collected and present some initial findings as to how the presence or absence of certain factors correlates with outcome. Then we suggest some implications for employees who wish to bring similar claims.

V. Outcomes: Which Factors Matter?

A majority of employees whose cases made it to the ALJ won. Of the 101 cases in our sample, 62% of employees won, while just 38% of employees lost (where “winning” is defined as getting a reinstatement order).[30] The frequency of employee wins may indicate that once they make it to an ALJ hearing, the NLRB General Counsel’s support and the law applied tend to give them a good chance of winning their cases. On the other hand, given the winnowing that occurs before this stage, leading to the NLRB General Counsel choosing to prosecute these cases, we might expect even higher win rates for the workers whose charges are heard before an ALJ.

Factors and Corresponding Outcomes

When we look to the data measured according to presence of a given factor, we can start to identify which factors correlate with employee success. Notably, in 75% of cases that employees won, the ALJ determined that there were written or verbal indications of animus from by the employer. ALJs almost never ruled for the employer after finding credible written or verbal indications of animus. In the rare cases where they did, the written or verbal indications of animus were sufficient to prove animus, but the employer was able to offer sufficient proof that they would have taken the adverse action regardless.

The presence or absence of false or pretextual reasons functioned similarly. In nearly 80% of cases where employees won, the ALJ determined that the employer had offered false, shifting, or pretextual reasons for the adverse action. ALJs often treat pretext as dispositive.[31] If they find that the employer’s proffered reason for the adverse action is pretextual, it is treated as sufficient to arrive at the conclusion that the adverse action was taken because of the protected activity.[32]

These results demonstrate the impact of written or verbal indications of animus or pretext, but also point to the high standards employees often must meet to vindicate their rights under the Act. Circumstantial factors can combine to sufficiently demonstrate animus in the absence of direct evidence; but most of the employees who won in our sample did so with either direct evidence of animus, employer pretext, or both.

The other factors are somewhat less conclusive. Although no ALJ found disparate treatment and still ruled for the employer, evidence of disparate treatment was also lacking in 59% of employee wins. In these cases, however, the employees typically also had evidence of pretextual or shifting reasons for the adverse action given, which likely made the absence of additional circumstantial factors less important. We can conclude that evidence of disparate treatment bolsters the strength of an employee’s case significantly, but is neither prerequisite nor panacea.

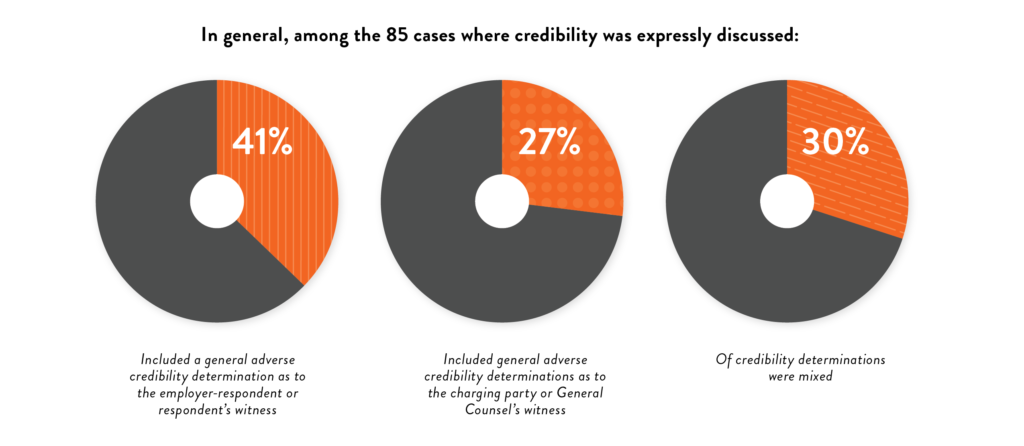

Credibility determinations were a factor in many of the ALJ decisions, perhaps necessarily so given the competing narratives often presented at the hearings. Of the employer wins, 61% included an adverse credibility determination against the employee, and of the employee wins, 59% included an adverse credibility determination against the employer. In general, among the eighty-five cases where credibility was expressly discussed, 41% included a general adverse credibility determination as to the employer-respondent or respondent’s witness, 27% included general adverse credibility determinations as to the charging party or General Counsel’s witness, and 30% of credibility determinations were mixed.

Finally, throughout these cases, we found that the most frequent reason that employees lost at the animus or employer burden stage was where the employer was able to present evidence, including credible testimony, of a lawful reason for the adverse action unrelated to the protected activity. For example, in AT&T Mobility Services, Inc. 20-CA-215835, although the employee was found to have engaged in protected activity, the employer was able to present credible evidence of frequent tardiness and no-call no-shows. Further, firing the employee was in line with the company’s progressive discipline policy. This evidence undercut the employee’s claim that the firing was due to animus towards protected activity, and the ALJ instead found that he had been fired for lawful reasons.

VI. How Are These Factors Analyzed?

In this section, we provide greater context for our quantitative findings with a qualitative analysis of how the ALJs applied the legal standards to the facts presented in these cases. After that, we consider the implications of our analysis and findings for workers.

Concerted Activities

The initial question of whether the employee’s activity is concerted and for mutual aid or protection may look like a relatively low bar to clear, but roughly 42% of employee losses occurred at this stage of the analysis. Indeed, this was the most common reason why employees lost in our sample. The analysis tends to break down into the “who” (is it concerted) and the “what/why” (is it for mutual aid or protection) of the activity, though ALJs often condense the two categories in their analysis. In this and the next section, we’ll review the current legal standards for each element of determining whether or not activity is concerted or engaged in for the purpose of mutual aid or protection, and provide some examples of how judges interpreted those standards.

- Legal Standards: Concerted Activity

The core requirement under Section 7 to protect workers is that the precipitating action must be (1) concerted and (2) engaged in for the purpose of mutual aid and protection. In the language of the statute, the activity must be “concerted” – that is, done with or on behalf of other people – but the statute itself does not offer a clear definition of what constitutes concerted activity. The legislative history of the statute suggests that Congress had “individuals united in terms of a common goal” in mind while drafting, but the specifics were left up to the NLRB to determine.[33] As the Board explained in Hoodview Vending Co., 359 NLRB 355, 357 (2012), “[g]enerally speaking, a conversation constitutes concerted activity when ‘engaged in with the object of initiating or inducing or preparing for group action or [when] it [has] some relation to group action in the interest of the employees.’”[34] Although closely related to the question of whether an action was engaged in for the purpose of mutual aid and protection, the two concepts are analytically distinct: the question of whether an action is “concerted” depends on the manner in which the action may be linked to those of co-workers, while mutual aid or protection depends on the goal of the action. Fresh & Easy Neighborhood Market, Inc., 361 NLRB 151, 152-53 (2014).

The Board has held that concerted activities are those actions which are “engaged in with or on the authority of other employees” and “not solely by and on behalf of the employee himself.” The Board has also repeatedly affirmed that the action must be evaluated holistically to determine whether it constitutes concerted activity for mutual aid or protection.[35] Judges often look to the manner of the action as objective evidence of concertedness: a petition signed by multiple employees, work stoppage, or common complaint voiced during a staff meeting will likely be considered concerted. But concerted activity can be found where an employee raises a complaint with a single co-worker, or where a single employee protests terms and conditions of employment common to all employees in front of their colleagues.[36] Employees do not need to explicitly state a concerted motivation, and any co-workers approached do not need to have an interest in the matter to make the activity concerted.[37] The underlying complaint does not even need to be meritorious, as long as it is still a logical outgrowth of concerns expressed by a group.[38]

- Inherently Concerted Activity

Certain types of activity, like complaints about wages or job security, are typically considered “inherently concerted”[39] and evidence of group action is not required. In Hoodview Vending Co., 359 NLRB 355, 357 (2012), the Board articulated the justifications for considering wages, scheduling, and job security inherently concerted: they are vital terms and conditions of employment and often a preamble to more formal organizing.[40] Wages are “the grist on which concerted activity feeds,” and “often preliminary to organizing or other action for mutual aid or protection.”[41] Job security similarly “concerns the very existence of the employment relationship,” while scheduling implicates “vital elements of employment – hours and working conditions” and is equally as likely as wages to inspire collective action.[42] As a result, these subjects are regarded as “inherently concerted,” meaning that any discussion of these topics among colleagues will be considered concerted even if group action is “nascent or not yet contemplated.”[43] Essentially, determining that a topic is inherently concerted allows the General Counsel to skip over the typical second step of the process of proving that the activity was engaged in for the purpose of mutual aid or protection.

- Example: Concerted Activities Analysis

An inherently concerted claim is not guaranteed to win – but it certainly helps. In McCarthy Law P.L.C., 28-CA-175313 & 28-CA-181381 (Jun. 30, 2017), for example, two employees sued for wrongful termination in violation of Section 7. The first employee, Kevin Wayne Hardin, was fired after submitting an anonymous note with concerns about management via an internal portal. When questioned about the note, Hardin vehemently denied writing it. The employer investigated further and ultimately terminated Hardin, ostensibly for violating a moonlighting policy. The General Counsel argued that the concerns voiced were a logical outgrowth of conversations he had with co-workers who had similar complaints. The judge concluded that the initial anonymous note had no evidence of concerted activity, as it was written in the first-person singular, and no additional evidence suggested that the employee was part of a known group or treated as a group. As the subject matter – concerns about mismanagement – was not inherently concerted, prior conversations that did not clearly contemplate group action did not qualify as concerted activity. As a result, the subsequent interrogation, investigation, and termination were not violations of 8(a)(1).

In this case, if the subject matter of the complaint were an inherently concerted topic like wages, hours, and working conditions, the General Counsel might have succeeded in arguing that the earlier conversations with his co-workers, before group action was contemplated, was enough – and the fact that he phrased his complaints in the first person might not have mattered. The investigation and ultimate termination were very clearly predicated on animus to the initial complaint about management conditions.

Mutual Aid or Protection

Besides being concerted, the activity must also be “for the purpose of…mutual aid or protection.” 29 U.S.C. §157. Although concerted activity is evaluated according to an objective standard, the employee’s goal in undertaking the activity still comes into play under the mutual aid or protection clause.

- Legal Standards: Mutual Aid or Protection

In Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB, 437 U.S. 556, 565 (1978), the Court identified the major outlines of the mutual aid or protection clause as follows: the employee or employees must seek to improve the terms and conditions of their employment, or otherwise improve “their lot as employees,” including through “channels outside the immediate employee-employer relationship.”[44] This includes support for employees of employers other than their own, appeals to administrative and judicial forums, and appeals directly to legislators. At some point, the relationship between the concerted activity and employees’ interests as employees may become “so attenuated that an activity cannot fairly be deemed to come within the mutual aid and protection clause.”[45] The question of when the activity crosses that line, however, is for the Board to determine “in the first instance as it considers the wide variety of cases that come before it.”[46]

As with other areas of labor law, however, an aspect of the Board’s standards for determining mutual aid or protection changed over the course of our research. Although the basic principles from Eastex remained the same, in 2019 the Board issued a decision in Amnesty International of the USA, Inc., 368 NLRB No. 112 (2019), rev. denied sub nom. Jarrar v. NLRB, 858 F. App’x 374 (D.C. Cir. 2021), holding that employee advocacy on behalf of those who are not statutory employees under the act exceeded the bounds of the mutual aid or protection clause.[47] Under this definition, advocacy for non-employee workers at the same employer – people like unpaid interns, consultants, prospective hires and contract employees – would not qualify for protection under the Act.[48] This decision was expressly overruled by the Board four years later in American Federation for Children, Inc., 372 NLRB No. 137 (2023), a move characterized by the Board as a return to “the traditional approach” and the solidarity principle as described by Judge Learned Hand in NLRB v. Peter Cailler Kohler Swiss Chocolates Co., 130 F.2d 503 (2d Cir. 1941):

“When all the other workmen in the ship make common cause with a fellow workman over his separate grievance, and go out on strike in his support, they engage in ‘concerted activity’ for ‘mutual aid or protection,’ even though the aggrieved workman is the only one of them who has any immediate stake in the outcome. The rest know that by their action each one of them assures himself, in case his turn ever comes, of the support for the one whom they are all then helping; and the solidarity so established is ‘mutual aid’ in the most literal sense, as nobody doubts. So too of those engaging in a ‘sympathy strike,’ or secondary boycott; the immediate quarrel does not itself concern them, but by extending the number of those who will make the enemy of one the enemy of all, the power of each is vastly increased.”

130 F.2d at 505-06. In American Federation for Children, Inc., the Board held that this principle clearly supports employee action on behalf of other workers, regardless of the nature of their employment relationship with the employer. As the Board put it, “[t]he question is simply whether in helping those persons, employees potentially aid and protect themselves, whether by directly improving their own terms and conditions of employment or by creating the possibility of future reciprocal support from others in their efforts to better working conditions.”[49]

Just as with other doctrinal departures from 2019, however, we did not see substantial changes in our dataset in cases issued before and after the release of Amnesty International in 2019.[50] There are many possible explanations for this, including that the doctrinal change likely affected only a modest subset of complaints. The patterns of judicial considerations to determine whether actions were engaged in for the purpose of “mutual aid or protection” that we did find in the dataset are detailed below.

- Factors that determine mutual aid or protection

To find shelter under the mutual aid and protection clause, the concerted activity must bear on the employee’s “interests as employees.”[51] Though this requirement may seem straightforward, it can sometimes be a contested and difficult question for ALJs. The requirement is consistent with the intent of the statute, but interpreting the requirement too narrowly can lead to outcomes that fail to account for the social pressures that workers face bringing complaints forward to management, and how that affects the way workers frame the issues they raise. The following cases are illustrative.

- Problem-Solving or Complaining

In Mat-Su Regional Medical Center, 19-CA-180385 (Jul. 7, 2017), the employee made comments to her supervisor about, among other things, an increased workload for case managers like her as a result of an eliminated position and policy change, and the need for private space to conduct sensitive work. These are comments about working conditions that affected not only the charging party but also her co-workers. The judge, however, found that none of the comments constituted concerted activity for mutual aid or protection. Instead, he found that the comments could not even be properly characterized as complaints, pointing to the charging party’s own characterization of the comments as “suggestions.”[52] He also found it suspect that the charging party did not testify to any specific prior conversations with co-workers about the issues, concluding that although a change “did indeed create more work for the case managers, neither Swan nor the case managers conceptualized this change as a problem requiring group action; rather, they conceptualized it as a problem that did not yet have a solution.”[53]

- Personal Issue or Workplace Issue

In Trey Harlin, P.C, 16-CA-171972 (Jun. 31, 2017), the judge found that the comments made to other employees had not been made with the purpose of seeking mutual aid or protection. Although the complainant’s credibility was called into question on a number of issues, including the legitimacy of some of her complaints, the concerted activity in question centered on a discussion she initiated with her co-workers about text messages she’d received from their boss that she believed may constitute sexual harassment. The General Counsel argued that even though the complainant did not expressly ask for assistance in the conversations, and even though those same co-workers ultimately turned against the complainant, the conversations about possible sexual harassment in the workplace still reflected concerted activity for the purpose of mutual aid or protection. The judge rejected these arguments, saying “I cannot credit [Complainant’s] claims that she raised the alleged sexual harassment with [colleagues] for any benefit but her own.”[54] In concluding that the complainant’s activity was not protected, the judge focused on language she had used about her boyfriend’s discomfort with the text messages, finding that “the inquiry was to satisfy her boyfriend’s concerns” and “no evidence reflects that the boyfriend was an employee under the Act.”[55] He came to this conclusion after affirming that employees are not required to explicitly state a concerted objective, and the analysis should focus on “whether the employee activity and matter concerning the workplace or employees’ interest as employees are linked.”[56] In this case, the activity was showing texts that the complainant believed constituted sexual harassment from a supervisor to two other female employees, supervised by the same person, for their opinion. The judge concluded nonetheless that she “was only considering what she should think about it, and perhaps her boyfriend,” and that it did not support an inference that she was seeking to initiate or induce group action.

The issue, though, was whether the claimant was discussing these texts with her co-workers “for. . . mutual aid or protection,” informed by whether the claimant is motivated by her interest as an employee.[57] In this context, the ALJ’s reference to her comments about her boyfriend’s discomfort with the text message is a red herring, distracting from the obvious implications of showing inappropriate text messages from a boss to two other female co-workers who work for the same boss. The #MeToo era revealed the insidious nature of sexual harassment, the likelihood of multiple victims of individual perpetrators, and the shame that many victims face in discussing their experiences at all. With this in mind, it is odd that the ALJ did not infer from the circumstances —talking to co-workers about possibly harassing texts sent by their boss— that “mutual aid and protection” was motivating the discussion.

- Concern About Working Conditions or Excuses for Performance

The question of whether the activity was “for. . . . mutual aid or protection” is about the employee’s motivation in discussing with others and making complaints. In some cases, ALJs will assess other possible motivations for the activity to determine whether mutual aid and protection is indeed a driving force. In Sierra Verde Plumbing Co., 28-CA-209991 (Nov. 14, 2018), for example, the complainant raised concerns about lacking necessary equipment, having to work overtime to complete assigned tasks, and a piecework pay rate to management. But even though the complaints themselves were focused on wages and working conditions, the judge nonetheless concluded that the complainant had not been engaged in concerted activity for the purpose of mutual aid or protection. Instead, the complaints were raised “on an ad hoc, individualized basis as an explanation or excuse when he . . . responded to accusations that he failed to complete a particular job.”[58] In reaching these conclusions, the judge repeatedly indicated that he did not find the complainant credible, and did credit another employee’s testimony that the complainant said he would go to the NLRB and would “own this company” in anger after he was fired for poor performance.

In looking at the employee’s motivation in conducting the concerted activity, the ALJ’s analysis can be seen as the inverse of Wright Line, which focuses on assessing the employer’s motivation in taking the adverse action. Just as a judge may look to express statements of animus, suspicious timing, pretext, and previous tolerance as evidence of improper employer motivation, similar factors may be assessed against complainants to identify improper motivations in raising complaints. In Sierra Verde, the judge functionally found that these same factors weighed against the sincerity of the underlying complaint. The judge noted that the verified complaints about working conditions – inadequate time and materials – were raised at a suspicious time. The statements were made as the employee was responding to complaints of poor work performance and were only raised at that time. In the context of a subsequent statement by the complainant that he would go to the NLRB and would “own the company,” – an express statement of animus made after he was fired – the judge found that “mutual aid or protection” was only a pretextual motivation for the underlying complaint.

- Implied or Explicit Motivations

The preceding cases demonstrate the fine line that employees seeking protection must walk to show legitimate motivations for concerted activities. For purposes of these claims, problems discussed with supervisors are better framed as complaints rather than an opportunity for collaborative problem solving. Discussions with co-workers should be frank, and employees should be explicit about their intention to solicit group action. At the same time, explicit statements about possible consequences for the illegal employer actions may lead judges to question the propriety of the underlying motivations.

Credibility

ALJs often offered multiple reasons when ruling against the charging-party employee. Often those reasons included some kind of credibility assessment against the employee. In 61% of employee losses, the judge explicitly identified the charging party as less credible than the employer or employer’s witnesses. Of course, many legal claims involve competing narratives where credibility determinations affect the outcome. But the way in which witness demeanor affected the credibility analysis in concerted-activity cases is worth particular attention.

- Legal Standards: Credibility

As with any legal claim, credibility determinations in NLRB proceedings are typically made up of several factors, including “the context of the witness’ testimony, the witness’ demeanor, the weight of the respective evidence, established or admitted facts, inherent probabilities and reasonable inferences that may be drawn from the record as a whole.” Hills & Dales General Hospital, 360 NLRB 611, 615 (2014). Judges often believe some but not all of a witness’ testimony, and credibility determinations are rarely all-or-nothing resolutions. Daikichi Sushi, 335 NLRB 622, 622 (2001). Where judges do weigh in on witness credibility, however, they often include impressions of general credibility based on witness demeanor on the stand. The Board typically defers to the judge’s credibility determinations on review and only rarely disturbs those findings in subsequent proceedings. Bridgeway Oldsmobile, 281 NLRB 12246, 1246 n. 1 (1986).

- Witness Demeanor Generally

In a variety of contexts, basing credibility determinations on witness “demeanor” has proven problematic, but it remains well-established in the legal system.[59] Very similar demeanor may generate different credibility determinations depending on who is doing the evaluation, particularly in situations where corroborating evidence is in short supply. It can also be one of the simplest determinations when direct evidence contradicts a person’s version of events. Even when reliable evidence clearly contradicts or supports one party’s version of events, however, judges may still evaluate and rely on witness demeanor in reaching their ultimate conclusion.

Indeed, some NLRB judges seem to go out of their way to draw adverse inferences about employee witnesses, perhaps to insulate their ruling from being reversed on appeal. For example, in American Classic Construction, Inc., Case 07-CA-143306 (Jul. 14, 2015), the complainant raised concerns about inspection of trucking equipment with co-workers, supervisors, and publicly on Facebook, shortly before being terminated. Nonetheless, the judge concluded that he was not fired for his protected concerted activity, noting that other employees involved in the complaint were not disciplined, written admissions by the complainant suggested he actually quit, and that the complainant had been involved in four contemporaneously documented expensive accidents in as many months leading up to the end of his employment. This is a case where it would be relatively straightforward to look primarily to documentation of the parties’ actions and motives in evidence, from text messages to incident reports to federal inspection paperwork, without relying heavily on witness demeanor to determine credibility.

Nonetheless, three pages of the seven-page bench decision issued by the judge focus heavily on witness credibility, a choice the judge justifies by noting that they had been “presented with two versions of certain events which cannot be reconciled.”[60] To be sure, the central conflict did boil down to whether the complainant had quit or been fired in a meeting, and the parties testified to two different versions of that final meeting. But as the judge had already noted, contemporaneous text exchanges clearly supported the employer-respondent’s version of events.[61] That the judge still offered individualized credibility determinations suggests either that witness demeanor remains highly relevant to judges even in cases with substantial corroborating evidence, that judges may use such determinations to minimize the risk of being overturned on appeal, or both.

- Tone

In drawing inferences about credibility, NLRB judges sometimes treat tone as a proxy for trustworthiness. For example, the judge in American Classic Construction noted that the complainant “sparred with Respondent’s counsel on cross-examination” and “became animated at various points.”[62] The judge also concluded that the “angry” tone of the complainant’s Facebook posts suggested that he was more likely to have lost his temper during the meeting than respondents, who “appeared calm throughout the hearing.”[63] These observations about the complainant were contrasted with the judge’s favorable impressions of the employer’s witnesses whose behavior was described variously as follows:

His demeanor on the witness

stand was steady and sure.”

“He testified in a forthright manner, and he

did not waver on cross-examination.”

“His testimony was straightforward

and had the ring of truth.”

“He appeared calm and sure of himself.”[64]

Those who appear calm, steady, and sure of themselves on the stand are thought to be reliable witnesses, as contrasted with the angry complainant. These kinds of observations of tonal contrast are common in opinions where the judge found either party unreliable. In Kingman Hospital, 28-CA-119580 & 28-CA-119729 (Feb. 20, 2015), for example, the judge similarly found it suspicious when a complainant “sparred” with opposing counsel on cross-examination, and noted that the “melodramatic and hyperbolic” tone, “glib testimony,” and inability “to give specific examples” of another witness similarly rendered their testimony unreliable.[65] These conclusions were contrasted with an apparently credible witness for the employer who “testified in a straightforward manner” and “was not shaken” by cross-examination.[66] Notably, the witness judged credible in Kingman Hospital had given testimony that was “contradicted by the documentary evidence in this case.”[67] The judge still determined the witness was credible overall.

The overall impression is clear: the complainant is animated, combative, and angry—and therefore not to be believed—while the credible employer is calm, steady, and self-assured. But in using tone to draw these inferences, these judges fail to consider whether there are reasons inherent in the dynamic between a fired employee and a manager with the weight of the employer behind them that might account for the difference in tone, rather than a difference in trustworthiness.

- Qualifying Language & Generalities

ALJs also drew adverse credibility determinations against employees for the use of certain kinds of language, in ways that may fail to take into account the reality of workers’ lives. Consider again Mat-Su Regional Medical Center, 19-CA-180385 (Jul. 7, 2017), where the charging-party employee made comments to her supervisor about various policies that interfered with workers’ ability to complete their required tasks on time. The charging party could not testify to specific conversations about the issues with her co-workers, but rather said that the issues were a topic of general discussion among her colleagues. The judge found that in the absence of corroborating testimony from her colleagues, these statements weighed against her credibility overall, and was “reticent, without more information, to find [general claims of discussions of the issues] indicative of concerted activities.”[68]

Similarly, the judge in American Classic Construction found the complainant’s use of “qualifying language (such as ‘to my knowledge’ and ‘to my understanding’) and generalities” on direct testimony suspicious.[69] Even where vague testimony is acknowledged candidly by the witness, as in Kingman Hospital, with an explicit admission that they are “not really good with specifics,” absence of detail can doom witness testimony to apparent untrustworthiness.[70] It may be that judges have unrealistic expectations of how much detail employees can be expected to remember about ordinary conversations with co-workers.

Animus & Affirmative Defenses

Once the General Counsel has proven that a disciplined employee has engaged in concerted activities, attention turns to employer knowledge and “animus”—the term used to refer to employer hostility to protected activity— before shifting the burden to the employer for an affirmative defense that the employee would have been terminated regardless of such animus.

In just over half the cases in our sample, judges expressly addressed written or verbal indications of animus in addition to circumstantial factors like suspicious timing, practice departures, and past tolerance. That number shot up to 75% percent in cases where employees won. It is unclear whether the affirmative evidence of animus in our sample is reflective of ignorance of the law, apathy toward it, or true hostility to protected activities – or perhaps some combination of the three. In Chip’s Wethersfield LLC, 01-CA-217597 (Sep. 25, 2019), for example, the employer admitted on the stand that he did not want the complainant to “advocate for everybody” and raise group complaints in individual meetings. The judge suggested that the employer presented this as evidence that the employee was engaged in some kind of misconduct, seemingly unaware that this is “precisely the sort of conduct that the Act protects.”[71]

The number of employers who maintained policies or practices of hostility to protected activity surprised us— until we recalled that nearly 50% of American workers report being specifically discouraged or prohibited from discussing their wage and salary information.[72] In Morgan Corp., 10-CA-250678 (Sep. 25, 2020), for example, the boss freely admitted that “he would not tolerate” wage discussions among the staff because “it caused ‘bad blood’” among employees.[73] Multiple supervisors at Morgan Corp. echoed the party line and actively told the complainant not to talk to his co-workers about wages.[74] If written or verbal indications of animus are proven, our analysis indicates that the employer is unlikely to meet their burden of proving sufficient legitimate reason for the adverse action.

Indeed, in 63 out of 71 cases in our sample where animus was proven, the employee won.[75] There were only two opinions and six charging parties in our data set in which the General Counsel successfully met their burden for proving animus but lost to an affirmative defense—that is, cases where the employer was able to prove that they would have taken the same adverse action for a legitimate reason, or that the employee behaved so egregiously in their conduct that they lost the protections of the act under Atlantic Steel.[76] Though this might suggest that affirmative defenses are rarely relevant, analysis of animus and affirmative defenses often went hand-in-hand since the underlying question is: what caused the adverse action, the unlawful interference with concerted activity (animus) or a legitimate business reason (affirmative defense)?

- Legal Standards: Animus

Animus is considered under a totality of the circumstances test. Wright Line, 251 NLRB 1083, 1089 (1980). Judges start by considering any affirmative evidence of animus in written or verbal communications. Affirmative evidence of animus can take the form of threats, interrogations, or statements or actions that create an impression of surveillance in the workplace. Sys-T-Mation, Inc. 198 NLRB 863, 864 (1972). Examples of circumstantial factors that judges consider to determine whether the employer is motivated by hostility (animus) to concerted activity include suspicious timing, false, shifting, or pretextual reasons, failure to investigate, practice departures, past tolerance, disparate treatment, and credibility. Tschiggfrie Properties, Ltd., 368 NLRB No. 120 (2019).

For an example of a holistic analysis of a record with clear “demonstrated animus,” consider Castro Valley Animal Hospital, 32-CA-251642 & 32-CA-251642 (Jul. 27, 2020). In this case, a receptionist at an animal hospital was removed from future work schedules two days after complaining to a co-worker about a lack of breaks. When asked why she had been removed, the focus of her manager’s text message response was “her need for scheduled breaks and lunches, and that everyone else at the facility was satisfied” without breaks. The manager expressly told the complainant not to discuss other employees when raising her complaints.[77] In addition to this written direct evidence of hostility toward the concerted activities of the complainant, the judge pointed to several supporting circumstantial factors, including:

- Temporal Proximity: the employee complainant was removed from the schedule two days after engaging in the concerted action, supporting a finding of unlawful motivation (citing Mondelez Global, LLC, 369 NLRB No. 46 (2020));

- False, Shifting, or Pretextual Reasons: the employer offered “several shifting explanations” for what he expected the employee to do after removal from the schedule, and the proffered reasons contrasted with the direct evidence of animus in text messages (citing GATX Logistics, Inc., 323 NLRB 328, 335-36 (1997); Cincinnati Truck Center, 315 NLRB 554, 556-57 (1994));

- Practice Departures/Past Tolerance: Employer claimed that the employee voluntarily resigned by virtue of refusing to perform assigned tasks without a pay raise for several weeks prior to termination, and claimed a history of tardiness, rudeness, and unwillingness to perform certain assigned tasks further justified removing her from the schedule. The judge found that the employer had never disciplined the employee for this behavior and never established that those tasks were essential to her employment;

- Disparate Treatment: The judge found that receptionists were regularly permitted to vary their job functions “depending on their desired interests,” and a similarly situated co-worker was allowed to opt out of the same tasks the employee declined to perform in the lead-up to her termination; and

- Credibility: the judge dismissed the employer’s claim that the employee actually resigned as “simply not true,” pointing to several inconsistencies between employer’s testimony, official statements, and written statements to support a general rejection of the alternative theories offered by employer.[78]

This example demonstrates the truly holistic nature of the inquiry; just as with credibility, even when documentary evidence clearly supports one party’s narrative, judges take their charge to evaluate animus on the totality of the circumstances seriously.

A similar pattern is found in cases where direct evidence of animus is discredited, and judges look to circumstantial evidence that might support an inference of animus. In Comprehensive Post-Acute Network LTD, 09-CA-213162 (Sept. 18, 2018), for example, the judge determined that the case turned on animus, and declined to credit any of the complainant’s claims that explicit verbal threats of retaliation were made in private meetings with her supervisors. The judge had already determined that the complainant was not a credible witness, but also looked to possible circumstantial evidence of animus in timing, disparate treatment, departure from established practices, or inappropriate penalties. Finding a three-month gap between the alleged threats and the ultimate adverse action, with “no credible evidence of animus in the interim,” the judge concluded that there was insufficient evidence of animus to satisfy the General Counsel’s burden.

- Legal Standards: Affirmative Defenses

An employer can still succeed, after the General Counsel makes a prima facie case, if they can prove that they would have taken the same action regardless of the protected activity. Wright Line, 251 NLRB 1083, 1089 (1980). The strength of the alternative explanation must echo the strength of the prima facie case; a weaker prima facie case requires a lower burden of proof for showing that they would have taken the adverse action regardless. Sasol North America Inc. v. NLRB, 275 F.3d 1106, 1113 (D.C. Cir. 2002).

A different kind of affirmative defense is one where the employer shows that the manner of the concerted activity was sufficiently offensive or inappropriate to lose the protections of the Act, even though the adverse action clearly arose from a concerted activity. Atlantic Steel, 245 NLRB 814 (1979). To evaluate whether the behavior should lose the protection of the Act, judges consider four factors: (1) the place of the action; (2) the subject matter of the action; (3) the nature of the outburst, and (4) the degree to which the outburst was provoked by an unfair labor practice.[79] Employees that engage in conduct that is deliberately deceptive or maliciously false, where there is no necessary link between the deception and the protected concerted activity, will also lose protections under the Act. Ogihara America Corp., 347 NLRB 110, 112-13 (2006). “Maliciously false” statements are those made with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard for their truth or falsity. TNT Logistics North America, 347 NLRB 568, 569 (2006). Employees can also lose protections for publicly disparaging their employer’s products or services without relating the complaints to working conditions. NLRB v. Local Union No. 1229 (“Jefferson Standard”), 346 US 464 (1953).

- Business Conditions or Employee Performance

When the employer brings an affirmative defense that the adverse action (often firing) was motivated by reasons other than animus to the protected concerted activity, there is closer focus on the individual employee and their work product, as well as on the business conditions that precipitated the adverse action. For example, in Parkway Florist, Inc., 06-CA-217020 & 06-CA-209583 (Dec. 12, 2018), the employer successfully showed that slow business conditions precipitated a reduction in work hours and subsequent termination. The judge found the florist’s explanation credible even when she hired a different person to complete the same tasks, finding that changes in the employer’s circumstances were sufficient to justify changing course. The judge also noted, however, that the sole proprietor’s “frustration and anger with employees’ daily work performance . . . run through this whole case and carry great explanatory power for events that the General Counsel has decided to prosecute as unfair labor practices.”[80] In conclusion, the judge found, it did not matter whether the complaints about the employees’ performance were legitimate, as much as it mattered that the employer believed they were legitimate when they decided to fire the employee.[81]

Similarly, in Cordua Restaurants, Inc., 16-161380 (Dec. 9, 2016), the one employee who lost their retaliation claim was the subject of a customer complaint about inappropriate language. In fact, the employer called the customer as a witness, and she testified to her complaint on the stand. The judge found numerous inconsistencies in the customer’s account of the incident that led to the complaint. But the employer was able to show that they regularly fired employees for customer complaints, and that they fired another employee for the same complaint who was not involved in concerted activities. The judge noted that evidence of animus was lacking before concluding, in essence, that consistently following even bad policies suggested that the termination was actually legitimate.

Sometimes the employer is able to point to termination procedures initiated prior to the concerted activity as proof of legitimate motivation. For example, in M&T Engineering & Construction, LLC, 14-CA-240972, 14-CA-241119, & 14-CA-240972 (Nov. 26, 2019), the employer was able to show clearly that they intended to fire and replace the employees for poor work product before anyone complained about their wages, and that the complaints and animus arose after management had decided to terminate the employees, and not before.

- Offensive or Inappropriate Complainant Behaviors

Evidence of unsavory employee behavior or questionable motives while engaging in concerted activities typically doomed a complainant’s case. In Sweitzer, Maher & Maher, 04-CA-139626 (Jun. 19, 2015), for example, the complainant was fired as a personal trainer after reporting that a co-worker was sending harassing sexual messages to another employee. On investigation, the employer found that the opposite was true – that the alleged victim had sent numerous sexually inappropriate messages to the accused. The original complainant had raised several concerns about sexual harassment more broadly in the gym in addition to the specific allegations against her co-worker but was fired for the false allegation specifically. According to the judge, the statements accusing a co-worker of sexual harassment were made with reckless disregard for their truth or falsity – even though he admitted she may not have known the truth – and thus the complainant’s activity lost the protections of the Act.[82]

Similarly, in Trey Harlin, P.C, 16-CA-171972 (Jun. 30, 2017), the judge did not credit the employee’s claim that she was motivated to seek mutual aid or protection in showing her co-workers inappropriate text messages from her boss after her colleagues reported that she treated the sexual harassment allegations as a shield against firing for performance issues. In reaching this conclusion, the judge noted that he did not find the claimant credible when she testified as to her motives, and only credited her testimony where it was corroborated by objective evidence.

In Harbor Rail Services Company, 25-CA-16376 & 25-CA-174952 (Apr. 28, 2017), the complainant lost protections under the Atlantic Steel framework for an outburst in the work area that included profanity and personal insults directed at the manager. Despite concluding that the underlying complainant about working through unpleasant weather conditions was concerted activity for the purpose of mutual aid or protection, the judge reflected that “the events at issue arose after [Manager] did not give [Complainant] his preferred job assignment, and [Complainant] was upset, particularly because it meant he would have to work with the other laborers out in the rain,” shortly before concluding that the refusal to return to work and shouted profanities were sufficiently offensive to lose the protections of the Act.[83]

Offensive behavior at the root of the alleged action may also color judges’ opinions in earlier stages of the analysis. In Ekhaya Youth Project, Inc., 15-CA-162082 & 15-CA-155131 (Jul 15, 2016), the judge found expressions of animus in the termination letters sent to employees but determined that the actual content of the conversations leading to the employees’ terminations was not concerted activity. In the alternative, the judge found that the actual content of the conversations – derogatory comments about a supervisor’s sexual orientation and complaints about inter-office dynamics, in addition to salary discussions – was sufficiently offensive and inappropriate to overcome any protection that concerted activity would be due.[84]

- Relative Believability of the Parties

The final stages of analysis often prompt close attention to both employee and employer behaviors and ordinary practices. Employers face scrutiny for past practices and policies when judges consider animus; employees typically face close scrutiny when the employer argues that they were nonetheless justified in the firing. But where employers may be able to point to mismanagement or irrational policies as evidence that they lacked particular animus against the employee-complainant, employees are expected to adhere to strict standards of behavior to retain the protections of the Act. This is a natural consequence of an at-will employment regime: almost any reason for firing an employee is acceptable, while employees must be perfect to preserve their rights and demonstrate that the proffered reason is pretext.

VII. Implications For Workers

For some employees experiencing mistreatment in the workplace, the National Labor Relations Act may offer a viable path for protection from retaliatory discharge. Although most charges will be settled or dismissed by regional directors, our research suggests that cases that do make it to a hearing have a good chance of getting an enforcement order requiring reinstatement and/or back pay. The NLRB’s substantive investigative procedure does not necessarily require separate representation to generate a successful outcome. Outside counsel may, however, help workers understand how to avoid certain pitfalls in the process. With or without counsel, our analysis suggests two particularly important elements to bolster when pursuing these claims at the NLRB: (1) the concerted nature of the claim, and (2) credibility.

Concerted Nature of the Claim

More employees lost on a determination that their activity was not sufficiently “concerted,” or was not directed at mutual aid, than on any other issue in our sample. Employees concerned about discharge for raising concerns about wages, hours, and working conditions should focus on generating evidence supporting the concerted nature of the claim. Courts considered everything from the use of plural versus singular nouns in complaints to how the employee complainant responded to others’ complaints in initial discussion to determine whether or not an activity was truly concerted. Employees that anticipate or experience retaliatory discharges for complaints about working conditions should try to document with whom they have discussed the issues, from whom they have heard similar complaints, and how the issue affects co-workers beyond the immediate employee.