Workplace Justice

It’s Too Hard for Workers to Get Justice

Too often, employers violate workers’ rights and get away with it. Workers who experience illegal treatment, such as harassment and wage theft, don’t always know how to fight back, or if they should even try. Many workers often have to sign away their rights as a condition of employment. Workers deserve the opportunity to get justice via access to the courts, where they have a shot at recovery, and where a jury can decide their case.

Worker Power and the Enforcement Gap

One potential source of worker power is the threat of financial and reputational consequences to the employer if they don’t treat workers well and violate their rights. But how often are there actually consequences for violating people’s rights at work?

The challenge is that in the United States, most enforcement of workplace law is done by private parties, not underfunded government agencies. That is, individuals whose rights are violated—often assisted by lawyers—are the ones who have to seek consequences for employers who violate the law, generally by bringing or threatening to bring a lawsuit. But the obstacles to individual employment lawsuits are many: judges too willing to bend over backwards to avoid “interfering” with employer decisions; workers forced to go before private arbitrators, not juries of their peers; arbitrary limits on the ability to recover damages.

So there is a huge enforcement gap: between the number of workers’ rights violations, and the workers who get justice. And this gap is self-reinforcing. Companies are often willing to break the law because the risk and consequences of being held legally accountable is so low. If the possibility of a lawsuit is not truly threatening to an employer, they will continue to violate people’s rights over and over. And they do.

By The Numbers

A majority of private-sector workers who are not unionized are prevented from holding their employers accountable in court by forced arbitration clauses. (EPI 2018)

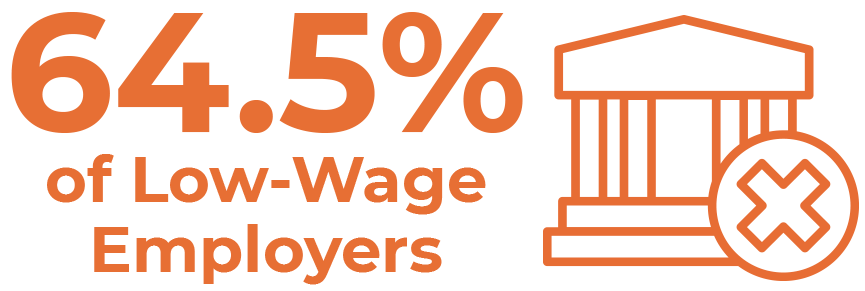

Forced arbitration is more common in low-wage workplaces; an estimated 64.5 percent of low-wage employers bar their workers from suing. (CPD and EPI 2019)

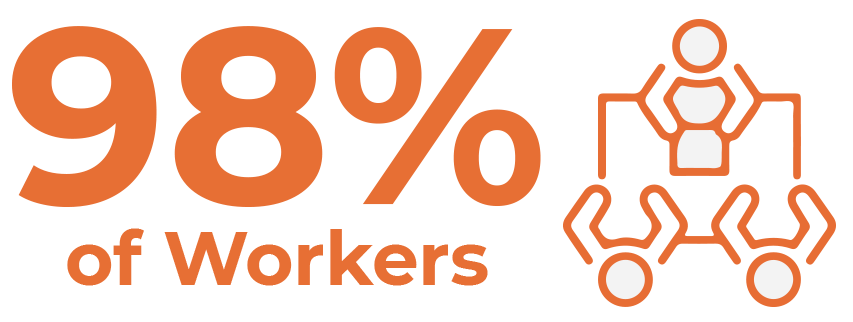

An estimated 98 percent of workers who would otherwise bring employment claims in court abandon their effort when the only option is arbitration (Estlund 2018), but even in federal court, plaintiffs’ win rate went from 70% in 1985 to just 30% in 2017. (Civil Justice Research Initiative 2019)

Ending Forced Arbitration

Forced arbitration denies America’s workers access to our nation’s civil justice system by requiring them to give up their rights to challenge their employer in court as a condition of taking a job.

Forced arbitration is anathema to our open justice system because it occurs in secret, private tribunals lacking important legal safeguards, such as the right to appeal the arbitrator’s decision, public access to arbitration proceedings that expose patterns of employer misconduct, and other guarantees ensuring a fair process that exist in a court of law. As a result, employers are shielded from public accountability for violating workers’ employment and civil rights.

Since its inception in 2008, the Institute has been working to end forced arbitration of workplace disputes, one of the most significant obstacles to the protection, enforcement, and vindication of employee rights.

Private Attorney General Model

In order to better enforce employment laws, states like California have passed laws that allow individual workers to sue employers on behalf of the state—essentially enabling individuals to act as a “private attorney general.”

- Unchecked Corporate Power: Forced arbitration, the enforcement crisis, and how workers are fighting back (Center for Popular Democracy and Economic Policy Institute 2019) This report highlights the challenge that forced arbitration has presented to workers’ rights, and how private attorney general laws offer a vehicle for enforcing the law.

- Possible paths after the Supreme Court’s Viking River Cruises decision – Though the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Viking River Cruises placed limits on states’ ability to provide individuals access to courts, Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence left open a potential window for individuals bringing these kinds of “private attorney general” claims to enforce the law.

Importance of the Civil Jury

The Seventh Amendment of the U.S. Constitution affords individuals the right to trial by jury in civil cases, ensuring fair and just application of the law. Workers are stripped of this constitutional right when they are forced to comply with arbitration clauses as a condition of their job. And even workers not subject to forced arbitration often can’t get a fair jury verdict, either because a judge improperly decides the case before it even gets to a jury or the jury’s verdict is reduced because of an outdated cap on damages. For more background on the importance of the civil jury, see The Civil Jury: Reviving an American Institution.

Summary Judgment. Motions for summary judgment asking the judge to throw out the case before it goes to a jury are more likely to be filed and granted in employment cases than in any other type of civil case filed in federal court, and grants of summary judgment rarely are overturned on appeal. Despite dedicated efforts to enforce the well-settled rules governing summary judgment, cases still can be derailed by adverse credibility inferences, the improper weighing of the evidence, and “problem doctrines.”

Damage Caps. As part of a compromise in the 1991 Civil Rights Act, Congress capped the amount that workers can recover in compensatory and punitive damages in discrimination lawsuits. These caps have not been adjusted for inflation since 1991, which means that the real amount that victims of discrimination can recover goes down every year. This limit on damages has a disproportionate effect on lower-wage workers who cannot recover much in back pay. And these damages apply regardless of how horrific the discriminatory behavior, whether it is a woman being sexually harassed, or an employee being penalized or even fired for their religious beliefs. For more on this issue, read Professor Lynn Zehrt’s article Twenty Years of Compromise: How the Caps on Damages in the Civil Rights Act of 1991 Codified Sex Discrimination.

Workplace Justice Resources

Other Issues

Support Our Work

invest in the future of workers’ rights advocacy. Support the Institute today.